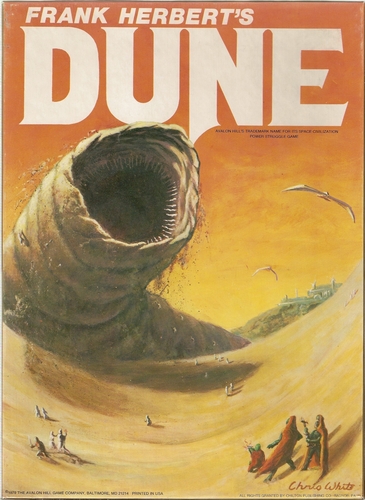

Unlike a lot of other pillars of nerd culture, Frank Herbert’s classic novel Dune is still waiting for its perfect adaptation. The 1984 David Lynch film is slog with amazing art direction, and the Sci-Fi channel miniseries reduced the scope of the novel lower than it could really bear. But if we expand the search to include other media, Dune has received two of the most important games of the last forty years. Westwood Studios’ Dune II: The Building of a Dynasty essentially codified real-time strategy games in the video game world. But Dune’s greatest adaptation might just be Dune the board game, published by Avalon Hill in 1979.

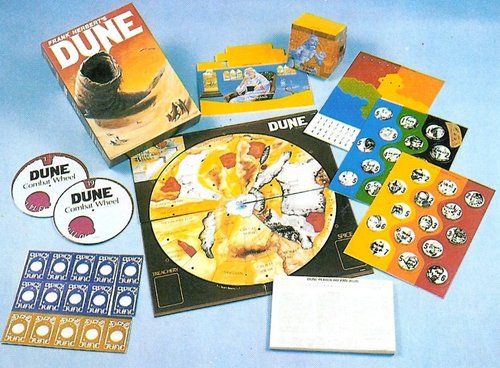

Designed by the same team that changed gaming forever with Cosmic Encounter, Dune is a monument of thematic gaming. Six factions from the novel square off on the planet of Arrakis: House Atreides, House Harkonnen, The Fremen, The Spacing Guild, The Bene Gesserit, and the Emperor’s forces. They seek to control Arrakis (also called Dune) so that they can control the flow of Spice, the substance that makes space travel possible and allows humans to expand their minds to new horizons. The board game takes place over up to fifteen rounds. Players buy new troops, move them around the board, and engage in combat to secure strongholds and new supplies of Spice, which allows them to buy more troops and bring back dead leaders. The winner is the person who controls three of Dune’s five strongholds at the end of a turn, although there are some special win conditions for some of the factions. The broad strokes of the game are actually quite abstract. The troops are mostly generic tokens, sort of a resource that can be spent in combat to control territories (more on combat in a minute). Likewise movement is very limited, allowing players the ability to move from just one territory to one other in a turn, as well as allowing them to bring troops from off the board into a single location.

However, woven into this very limited system are numerous mechanics that transport the whole thing to Herbert’s world. Some of these are tied to the board and how Spice appears. There is a constant windstorm that circles the board, destroying troops and consuming Spice that it passes over. Troops can take shelter in certain spaces, but it’s a constant consideration, pushing players to take risks when they otherwise might not. There is also what is called the “Spice Blow,” a card draw every turn that makes new Spice appear on the board. Every so often one of the Spice Blows is accompanied by Shai-Hulud, one of the great sandworms of Dune, which destroy everything beneath them. These are omnipresent factors in the novel, and the game recreates them with aplomb.

But much of the strategy and thematic depth of Dune comes from the factions themselves. Having already designed Cosmic Encounter, the Future Pastimes team was no stranger to player powers. But Dune embraces these differences to a much deeper effect. House Atreides has access to information that would otherwise be hidden. The Harkonnens are given a much larger hand of Treachery Cards, allowing them to pull more nasty tricks. The Spacing Guild controls the highways of space, and so they receive Spice whenever someone ships onto Dune. The Fremen, being native to Dune, don’t need to ship units to the planet, and are able to move much faster. The Emperor receives Spice for the purchase of treachery cards. Finally, the Bene Gesserit are able to force players to do their bidding, and are able to execute a secret victory if at the beginning of the game they correctly predict who will win and on what round they will do it. There are other powers at work for each faction, and their setup at the beginning of the game means they will all be in different states when the game begins.

It is impossible to overstate how well these factions are designed. Each of them recreates the abilities and weaknesses of their counterparts in the novel so thoroughly that the players find themselves thinking like their factions. The Harkonnen player will naturally be given to aggressive military moves and dirty tricks. The Bene Gesserit player will begin to subtly manipulate others to compel them to do what they want. The Emperor and Spacing Guild can use their great wealth of bribe the other players into doing their bidding as well. As alliances form, the game will also reward certain combinations over others, many of which line up with the novel as well. The Atreides and the Fremen for example have a lot of possibilities, and the Harkonnen and the Emperor are a formidable combo.

That’s right, alliances are a pivotal part of Dune as they are in Cosmic Encounter. Whenever a sandworm appears, the players are forced into a nexus, where they can formally ally with each other, giving each other special benefits. This also means that it’s extremely common for more than one player to win at the same time. This is an endlessly fascinating part of the game to me. It is almost always better to work with someone else than on your own, unless you are in a very good position. The powers granted by allies are sometimes useful enough that temporary alliances are worth forming just so you can use specific powers until you don’t need them anymore. Then you can find a new ally at the next nexus. When combined with the nature of deals, which in this game are always binding, and Dune has some of the most subtle and well-executed interaction I’ve ever seen in a board game.

Another brilliant element is the combat. There are two combat wheels, and when combat begins each player secretly picks how many of their troops in the territory they are willing to commit. They can also use the strength of a leader and weapon cards. Once both players reveal their battle plan, the person with the lower total must remove all of their troops from the territory, while the winner loses just the troops they committed. This creates a huge amount of tension, since new troops cost a lot of Spice and are a precious commodity. How much should one commit? Enough to win might mean that there won’t be much left to hold the territory. The added tension of the leaders, who may be traitors for the other faction and cause you to lose automatically, is delicious. And the weapon cards add another layer of double-guessing.

If it is not obvious already, Dune is a game of hidden information. There is very little random chance in the game, but it’s loaded with secrets. Everyone has their own plans, which dovetail into plans for alliances and enemies alike. It truly is a game of wheels within wheels, different plots that fall into place and are undone by a moment of delicious reversal. Because of this, Dune tends to play out in a rhythm of big moments. A player will get their strategy lined up for a big push toward victory, and will find themselves almost there…until they find themselves at the wrong end of a lasegun explosion. These moments can be crushing for a good stretch of the game, though as the game goes on it is often possible to recover and have another chance. It is not a game for those who like to have a sure thing, because every decision is made with roughly a quarter of the necessary information.

Dune is regarded as one of the greatest designs of all time, and it’s not hard to see why. For all of its thematic detail, it is actually quite streamlined, with an almost Eurogame feeling in its abstraction. I’ve even played with people who felt the game was a bit too simple, since almost all of its depth comes in the interaction of the players and the possibilities of alliances. Still, although the game was ahead of its time, it was published in 1979, and it shows. It really requires six players to work best, though five will do in a pinch. The instant win condition means the game is as likely to take two hours as it is six, and it requires the player to track a lot of information on a piece of paper. This is probably the best way to manage the protean nature of the game, but it will put off some modern gamers. The rules as written in the original Avalon Hill edition are notorious leaky, able to explain the broad strokes of the game but leaving some common interactions murky. It’s not helped by the presence of optional rules (which I always use) and controversial advanced rules, which I’ve mostly left alone. One of the great quests of the Dune page on Board Game Geek is to find a unified rewritten ruleset that irons out these kinks, but by its very nature Dune resists such efforts. A certain amount of flexibility is the best medicine.

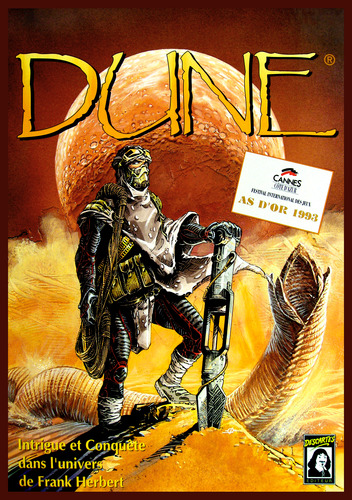

Now for the really frustrating part: Dune is hard to find. It has been out of print for decades now, and the Herbert estate is unwilling to allow a new version to be published. Still, the game was in print for many years, and used copies are not uncommon, though they can be expensive. Aside from the version published by Avalon Hill, there is another version that was published by the French publisher Descartes, with French components and the two expansions, though most players are lukewarm on those. Still either edition is great, and a copy of one of them will set you back roughly $80-$100. There is also a “rethemed” version called Rex from Fantasy Flight Games, published in their Twilight Imperium universe. This works for some people, and it’s much easier to find, but it’s a poor substitute overall. The design changes threw the game out of balance for me, and the good parts still feel ersatz and ill-fitting. There is only one Dune, and it works best in its original form.

It is impressive enough that the designers were able to recreate the setting so faithfully, but it is more remarkable that the original themes of the novel are so strong in board game form. The intense scarcity and environmental aspects of the book are here, the plots of the powerful are thrown into disarray by unlikely events, and the wheels-within-wheels scheming that fills the book also fills the game table. It’s an outstanding game, one that continues to loom large even though it is out of print and nearly 40 years old.